The Irish violently resisted English conquest, but each effort to resist ended in defeat. Each defeat led to the confiscation of lands of rebellious clans, which led to further rebellions and each, being Irish defeats, led to further confiscations.

The Irish pushed off historic clan land, and the land was sold by England to English land speculators. The land was often given to creditors of England to reduce national debt, or given to English soldiers who went unpaid for years of Irish wars.

After few centuries of this, Ireland was owned by relatively small number of English, and Irish were tenants of their own land.

The English referred to these lands as “plantations” – not because they were planting crops, but because planned to plant people on these lands.

The English were doing the same thing at the same time in North America – establishing plantations in Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and elsewhere.

Most English settlers wanted no part of these plantations in Ireland. Those English inclined to leave England, jumped across Atlantic and moved to North America.

These plantations were attractive, though, to the Scots. There was widespread poverty in Scotland. Scottish farms were often small and unproductive. Scottish tenant farmers were being evicted, with the landlords substituting sheep for the evicted tenants. Many Scots moved to Ireland and became tenants in these plantation farms. Others moved to Ireland and became merchants in the towns growing in Ireland. Even more moved directly to North America – either to the United States or Canada.

I will tell you about two Scottish families who moved to Ireland. These are the Hutchison and Jackson families, both of which lived for many generations in the Scottish Lowlands.

Scottish families were Catholic until the late 16th and early 17th Centuries, as were most inhabitants of the British Isles. But during the Reformation movement, most Scots in Lowlands became Presbyterian Protestants. The Hutchisons and the Jacksons were not exceptions – they became Presbyterians.

The Hutchison family moved from Scotland to Ireland in the 1600s. Cyrus Hutchison was born in 1690 in Carrickfergus. He married Margaret Lisle, who was likewise born in County Antrim from parents who were born in Scotland.

Cyrus and Margaret had a daughter Elizabeth, born in Ireland in 1737.

The Jackson family also left Scotland in the late 1600s. Hugh Jackson became a linen weaver and merchant in Carrickfergus. Hugh was born in Ireland, from parents born in Scotland.

Hugh Jackson had four sons, all born in Ireland. This third son was named Andrew.

Andrew Jackson married Elizabeth Hutchison in Belfast in 1760. Andrew and Elizabeth lived in Carrickfergus. They had three sons – Hugh, Robert and Andrew. The entire family moved to United States in 1760.

Hugh and Robert were both born in Ireland. Young Andrew’s place of birth is somewhat of a mystery. Some evidence suggests that he too was born Ireland. Other says North Carolina. There is even a hint that he was born over the Atlantic Ocean, while his family migrated from Ireland to North Carolina.

The elder Andrew was killed while young Andrew a boy. The eldest son Hugh Jackson died of heat exhaustion while serving in an American regiment in the Revolutionary War.

Robert and young Andrew also served in the Revolutionary army. Andrew was only 13 when he enlisted. Robert and Andrew were captured by the British during the war, and both were imprisoned. Robert died of small pox while in prison.

Young Andrew survived the war but carried a scar from a beating given to him from a British officer. Andrew’s mother Elizabeth died of cholera during the war. Young Andrew was the family’s only survivor of the Revolutionary War.

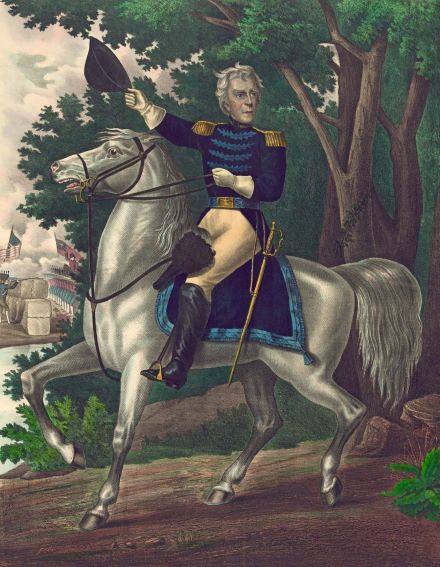

Most of you know the rest of the story. Andrew studied law; he moved to Tennessee; he was elected to legislature; he fought in many Indian wars; and he became general first in the militia and then in the United States army.

He became an American hero when his army defeated the British in the Battle of New Orleans. He later was elected President of the United States for two terms. Today he is most famous for being on the $20 bill.

His mother, father and two brothers were born in Ireland. Andrew too may have been born in Ireland. He claimed American birth during presidential campaign – there were birthers even then.

The only way to know for certain where he was born is to ask his mother Elizabeth. And she and I not on speaking terms.

Andrew Jackson not thought of as a hero in Ireland. He is not thought of much at all. His home in Carrickfergus was home of one family or another for nearly two more centuries after the family left for America.

I’m not sure why Andrew Jackson is not revered in Ireland, at least not in the same way as John Kennedy. I suspect that to the extent Irish Catholics think of Andrew Jackson at all, they think of him as a Scots-Irish Protestant.

And what separates Northern Irish Protestants from Irish Catholics is not religion. It is national identity. Irish Catholics think of themselves as “Irish”. Northern Irish Protestants think of themselves as “British”. Andrew Jackson was a Scots-Irish Protestant, but he was also passionately anti-British.

Now let’s fast forward to 1943. A few million American soldiers were in Britain preparing for the invasion of France. They were disbursed throughout Great Britain, going through last minute training and preparing for D-Day.

A unit of U.S. Rangers was stationed in Carrickfergus. They were surprised to discover that an old home on Boneybefore Street was the family home of President Andrew Jackson.

Despite the long hours these soldiers spent in training, they devoted their off-duty hours to restoring the Jackson home. Today, the house itself is in its original state – the same as it was when the Jacksons lived there.

Andrew Jackson is a well-known historical figure. But it is little known is that he was an Irish man – the first Irish American to be elected President.