The story in The Cornfield of combat at Antietam ended about 7:30 am, at the end of the fighting at the cornfield. Half of the men who went into the cornfield were, by then, dead or wounded. Those who survived without a physical wound were physically and mentally exhausted and could fight no longer. Historians no longer referred to the field as David Miller’s cornfield. The site earned a capital C. Thereafter called The Cornfield.

The battle elsewhere continued the rest of the day, for ten or eleven more hours. It shifted south, to Mumma farm, the west woods, Dunker Church, the sunken road, Piper farm, the Lower Bridge, and the Otto farm. There was never any coordination of the Union assaults, each coming one at a time.

The intense fighting stopped by 6:00 pm, with only sporadic musket and cannon fire for the remainder of the day. The battle ended in a tactical draw, in that the Confederate army at essentially the same place it was when the day began. The Union army had crossed Antietam but remained parallel to the Confederate lines.

Close to 6,500 men were killed or mortally wounded on that day, and 20,000 more suffered wounds from which they could recover. These numbers made September 17, 1862, the deadliest day in American military history. No day – before or since – have more Americans died or suffered wounds in battle.

General McClellan and the northern press puffed the battle into a great victory. It was not, although it seemed so after the disaster at Manassas and Lee’s invasion of Maryland. It was enough of a victory for President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation freeing all slaves in the rebelling states. The war to preserve the union now became, in addition, the war to end slavery.

It certainly could have worse for the Union. It would have been were it not for the fortuitous discovery of Special Order 191. It could also have been much better for the Union – had McClellan moved quicker and with greater force to South Mountain; or attacked Lee at Sharpsburg on the afternoon of September 15th or morning of September 16th, before Jackson’s half of the Rebel army arrived; or coordinated the attacks on multiple fronts on September 17th, instead of launching assaults one at a time; or resumed the assaults on the 18th, particularly with the 20,000 soldiers he held in reserve on the 17th; or immediately crossed the Potomac and pursued Lee’s retreating army.

It was this last failure that triggered Lincoln’s decision to fire McClellan. Lincoln understood, as few of his generals did, that the war would not end until Lee’s army was destroyed.

The Army of the Potomac did not leave Maryland for Virginia until October 26th. Even then it took the army six days to cross the Potomac – Lee got his entire army across in a single night.

Despite the various “what ifs,” Antietam did not end the war. It would take another two years and eight months.

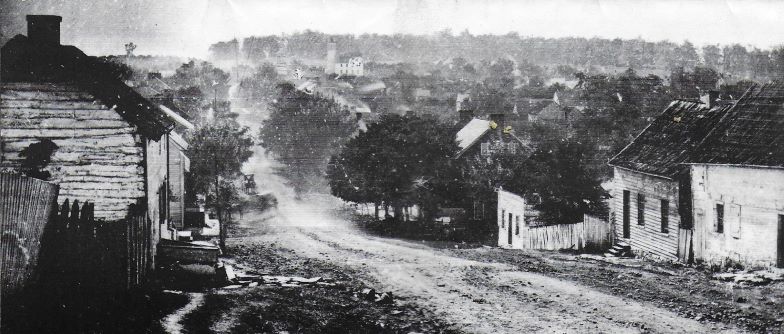

Photograph at top and of Town of Sharpsburg by Alexander Gardner, September, 1862. Photograph of the Cornfield by Stephanie Heidbrener for National Parks Conservation Association. The Miller farm is in the background