When What You Know To Be True Is Not True

[2019 editor’s note: I posted an entry dealing with a lesson not learned by a member of the Bush Administration. That portion of the post is no longer relevant to anything and so I am not re-posting it. But my “lesson” remains, so I am re-posting that portion of the original blog entry.]

I re-learned a valuable lesson today – always check and double check your facts. Knowing the facts can help you avoid making a serious mistake.

I have a passion for history and enjoy telling stories from histories. Stories about people in the past help us understand that those people are just as real, just as human, as we. I plan to tell some of those stories at the Café from time to time.

To titillate Café visitors, I thought I would tell the story of the derivation of the word hooker as a slang for a prostitute. I knew that the word derived from General Joe Hooker, a celebrated general in the Union Army during the Civil War. I remembered three different stories, and I began my research to find which was the most plausible connection between the general and the slang.

Story One: Many women followed armies in the 19th Century and earlier. Some of these were prostitutes but most were not. Some women made their living doing laundry for soldiers. In eras before organized commissaries, soldiers had to cook for themselves in the field. This provided a ready market for some women who, for a modest fee, cooked for squads of soldiers. Other women followed armies with humanitarian motives. Sick and wounded soldiers were cared for, not by an army medical corps, but by women who followed marching armies.

During General Hooker’s brief tenure as commander of the Army of the Potomac, the women following the army came to be known as Hooker’s Division or Hookers. Eventually, the nickname stuck to describe prostitutes.

Story Two: In the early years of the war, Hooker was commander of a portion of the volunteer army assigned to Washington, D.C. Hooker had to find housing for these men and put many of them up in Washington’s high crime, red light district. This neighborhood was then known as Murder Bay but soon became known as Hooker’s Division. Residents, in turn, became known as hookers.

Story Three: General Hooker was not a man of impeccable moral character. He was a hard drinker and frequent visitor of houses of prostitution – sat Murder Bay and elsewhere. Prostitutes were frequent visitors of his headquarters during his command of the army. These women became known as hookers.

I spent a modest amount of time in research and I was somewhat surprised at the result. What I discovered was that none of these three stories were true. What I had known to be true turned out not to be.

It turns out that the word hooker was in use, and can be found in print, several years before the American Civil War. For example, an 1845 publication described an interesting travel route: ”If he comes by way of Norfolk, he will find any number of pretty Hookers in the Brick row not far from French’s hotel”.

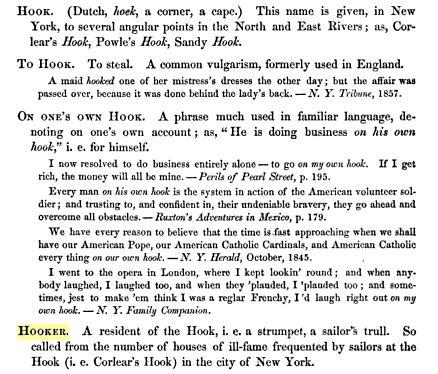

The word is also in Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms, A Glossary of Words and Phrases, published in 1859 (shown at left), as ”one who hooks”, and a prostitute ”who hooks, or snares, clients”. Bartlett’s suggest the word is derived from several disreputable neighborhoods in New York City.

It is also possible that the term originated with the slang language of thieves and pickpockets in England. To snag something from another’s house through a window or from their yard with a stick, or to purloin anything from another’s pocket (also known as dipping among pickpockets) came to be called hooking. The association of the lower classes of people – thieves, pickpockets, muggers and prostitutes – may have resulted in the interchangeable use of the term from one trade to another.

I found this all a bit disconcerting. First because it killed my story idea for the Wolverine Café. Second because it meant that something I knew was true was actually not!

Fighting Joe Hooker

Joe Hooker is one of those people who prove that everyone will, eventually, rise to their own level of mediocrity. (Isn’t this one of Murphy’s Laws?)

Hooker was a West Point graduate and was decorated for bravery in the Mexican War. He became a colonel in a California militia unit at the outset of the war, but was given command of a brigade, with the rank of brigadier general, in 1861.

He served ably as a brigade commander in the Peninsula Campaign, so was promoted to division commander. He was an excellent division commander, so was promoted to major general and given command of an entire army corps. After his corps served well at South Mountain and Antietam, and after General Burnside demonstrated incompetence at Fredericksburg, Hooker was given command of the entire Army of the Potomac.

As commander of the entire army, Hooker reached his level of mediocrity. Hooker made some disastrous decisions in and around Chancellorsville and his army was soundly defeated by the Confederates. Hooker was replaced by George Meade shortly before Gettysburg.

Hooker’s nickname was Fighting Joe, which had nothing to do with his propensity to fight. Rather, it was the result of a typographical error. A journalist’s dispatch, from the Virginia Peninsula, included within the text: ”Fighting – Joe Hooker”. The dispatch described, in shorthand, that there was fighting and that there was Joe Hooker. But in print, the dash was omitted, and the article referred to ”Fighting Joe Hooker”. He was thereafter known as ”Fighting Joe”.