Masonic and Irish 1798 Martyr

This a from an oral presentation made to the Grand Lodge of New Mexico Ancient Free & Accepted Masons, on October 6, 2016 in Albuquerque. I was asked to talk about the Masons in Ireland or, perhaps, similar options. I looked at several possibilities as subject matters for the talk. I researched those options and I looked at a number of others.

As I focused my thinking, and synthesized all that I learned about masons, I decided to simply talk about two masons in Ireland. And I don’t even know the name of the first mason I talked about. His story is at this link.

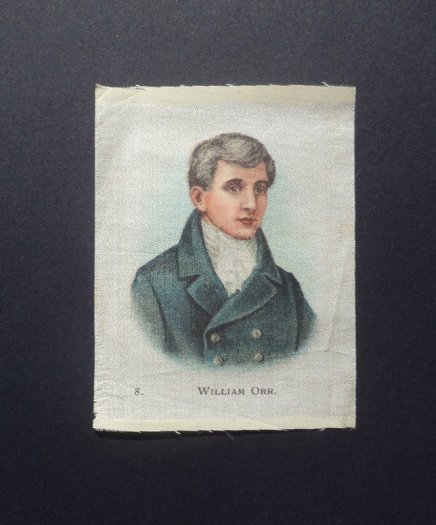

The second mason was William Orr. His story is told as if it were the transcripts of my talk to the New Mexico Masons.

The 98

Ireland’s 1798 Rebellion occurred a decade or so after the American Revolution and the French Revolution. There is a common thread. Faith in Supreme Being, with that faith manifested in accordance with individual’s belief. Basic human rights were granted by the Creator, and not by kings and lords.

This does not seem such a radical position today, but it was certainly radical in the 18th Century.

These concepts are incorporated in America’s Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution. It should be obvious that they are entirely consistent with the basic principles of freemasons. And indeed, there were freemasons – like George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and James Monroe – actively involved in the creation of the United States.

The English were scared to death that the same movement would take hold in Ireland. And indeed it did.

In 1791, a group of men met in Belfast and formed the Society of United Irishmen. At the time, Ireland was a colony of England, governed much the way as the 13 American colonies. The Irish sovereign was the king of England. Ireland had its own parliament, but it was dominated by Irish Protestant landlords.

The United Irishmen published a 3 point manifesto:

1. English control over Ireland was so great that it required a unified effort of all Irish to balance it.

2. The only way that could be done is with a complete and radical reform of the Irish parliament.

3. No such reform would be just without the participation of Irishmen of every religious persuasion.

The United Irishmen simply wanted a freer society, governed in a way that represented all people, with less dictatorial rule and more civil liberties.

Ireland at the time was about 80% or so Catholic, and Catholics were totally excluded from participation in the political process at the time. There were many organizations of Irish Catholics pushing for the same thing. But with the United Irishmen, Ireland had, for perhaps the first time, Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics seeking the same end.

Many, but certainly not all, of the United Irishmen were masons. And, as in the case of the American Revolution, it should be clear why. What the United Irishmen wanted was entirely consistent with masonry.

As a reminder, this was a time when masons opened up its membership to people who were not masons by trade. Men who demonstrated good character and who accepted the principles of masonry could become masons. In the parlance of the times, these men were ‘gentlemen’.

The masons of Ireland then were almost entirely Protestant. There were two reasons for this. One is that there were very few Irish Catholics at the time that could be called ‘gentlemen’.

This is not because they lacked character. It was because there were very few Catholics who had any form of social standing or education or occupation which could give them the status of being a ‘gentleman’. Most Irish Catholics were laborers on Protestant owned farms or were tenant farmers of a few acres of land.

The other reason was the attitude of the Catholic Church towards masons. Masons never prohibited Catholics from joining. But the Catholic Church prohibited Catholics from becoming masons, under penalty of excommunication.

The British government banned the United Irishmen, and it thus became a secret society. Members swore an oath of allegiance and of secrecy. The British then made it a crime, punishable by death, to administer any unlawful oath.

Which brings us to William Orr. He was from County Antrim, the son of a farmer. He too was a relatively prosperous farmer. He was a Presbyterian. He was the Worshipful Master of his local masonic lodge. And he was an active United Irishman.

In 1797, Orr was arrested for administering the United Irishmen’s oath to a man who, it turns out, was an informant for the British government.

Here is the oath:

“In the presence of God, I do voluntarily declare that I will persevere in endeavoring to form a brotherhood of affection amongst Irishmen of every religious persuasion, and that I will also persevere in my endeavors to obtain an equal, full, and adequate representation of all the people of Ireland.”

The evidence against Orr was perjured. He may indeed have administered the oath to someone else. And a United Irishman may have administered an oath to the informant. But it wasn’t Orr.

But the British wanted to set an example, and William Orr was convicted and sentenced to hang.

After sentencing, Orr gave a very passionate speech, as passionate as any given by an American patriot during America’s fight for freedom. I won’t read you the entire speech, but I will read you one sentence of it:

“If to have loved my country – to have known its wrongs – to have felt the injuries of the persecuted Catholics, and to have united with them and all other religious persuasions in the most orderly and least sanguinary means of procuring redress – if those be felonies, I am a felon, but not otherwise.”

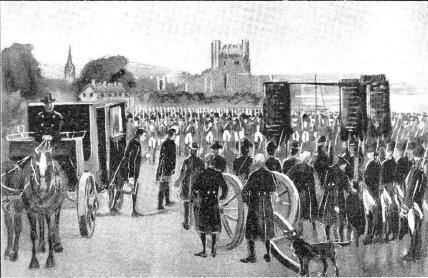

There was a huge turnout for the hanging in Carrickfergus, with almost all in attendance being in support of Orr. The British feared an uprising and many Redcoats were ready.

While standing on the gallows, Orr said:

“I am no traitor. I die as a persecuted man for a persecuted country. Great Jehovah receive my soul.”

After the hanging, Orr was given a masonic funeral. Orr was 31 years old.

Rebellion finally broke out in 1798. It was a sporadic but intense affair. Fighting broke out in one part of Ireland, put down by British soldiers, and then broke out in yet another part, with the same result. There was no command and control structure, and units were self-organized. The uprising began in the early summer and extended well into the fall. By extending past harvest, thousands died from starvation in the following winter and spring.

As the rebellion was crushed, Irish rebels were executed – often on the spot on the battlefield. Many others were rounded up and hanged. William Orr was the first martyr for the cause, but there were many, many others.

It’s a reminder of what would have happened to American patriots had we lost the American Revolution.